Two decades after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Robert F. Kennedy warned the world about the catastrophic danger of nuclear proliferation. In his 1965 speech addressing the urgent need to control the spread of nuclear weapons, he stated, “…the proliferation of nuclear weapons immensely increases the chances that the world might stumble into catastrophe.” Today, Kennedy’s stark warning holds true now more than ever, as now nine countries possess nuclear weapons. However, not only does his speech illuminate the dangers that lie ahead, it details the devastation that is sure to follow:

“Eighty million Americans, and hundreds of millions of other people, would die within the first twenty-four hours of a full-scale nuclear exchange. And as Chairman Khrushchev once said, ‘the survivors would envy the dead.’”

His words continue to serve as a reminder to humanity that the human cost of nuclear weapons does not end with the blast. The lasting consequences that Kennedy warned about are reflected in the experiences of hibakusha (被爆者), or atomic bomb survivors, whose stories illustrate the enduring human rights cost of nuclear weapons.

According to the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, hibakusha are people who fit into one of these four categories:

- Those who were directly in Hiroshima or Nagasaki at the time of the bombing

- Those who entered the affected areas shortly after the bombings

- Exposed to radiation through relief work, cleaning, or being in the “black rain” areas

- Unborn children of those who fit into the first three categories at the time of the bombing

Beyond the immediate physical and physical trauma, hibakusha faced widespread societal discrimination. Fears of radiation contamination pushed potential employers and marriages away. Kunihiko Sakuma recalls the rumours he heard growing up, that survivors were diseased and that their future children would be ‘tainted’ by radiation. Survivors endured guilt, illness, and poverty, often sacrificing their dreams due to widespread societal misunderstanding and discrimination.

Beyond official definitions, the definition of hibakusha has since broadened to include anyone exposed to radiation from nuclear weapons (through their use, testing, or production, or from activities related to nuclear power and waste management). This broader definition further illustrates the impact that nuclear weapons have on human kind. For example, the U.S. nuclear testing on the Marshall Islands caused the Marshallese people to be exposed to dangerous levels of radiation, displaced from their homes, and caused severe environmental effects. Similarly, radioactive violence subjected on Indigenous communities as a result of nuclear testing and uranium mining have led to widespread suffering.

The experiences of hibakusha around the world reveal that the legacy of nuclear weapons is measured not only in immediate deaths, but in decades of suffering and injustice. Their stories are powerful reminders to approach national security decisions with human rights in mind. Recognizing these long-term consequences is essential for developing policies that prevent future suffering.

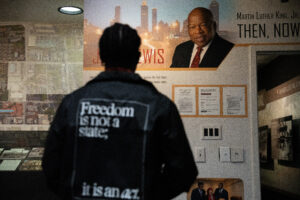

My own work over the past several years has shaped my perspective on the human impact of nuclear and national security policy. During my time as a John Lewis Young Leaders Fellow, I conducted data-driven analyses of human rights issues and developed a quantifiable metric to identify patterns in human rights respect over time. Later, as a Public Policy International Affairs (PPIA) Fellow, I gained experience in studying public policy. Both instances have heightened my awareness of the ways policy decisions impact communities. I apply this lens to my focus on national security and nuclear policy, where it is clear that strategic considerations intersect with the real, lived experiences of populations affected by nuclear weapons.